Or: Sometimes You Don’t Need a Computer, Just a Brain

I was watching an episode of 8 Out Of 10 Cats Does Countdown the other night1 and I was wondering: what’s the hardest hand you can be dealt in a Countdown letters game?

Sometimes it’s possible to get fixated on a particular way of solving a problem, without having yet fully thought-through it. That’s what happened to me, because the first thing I did was start to write a computer program to solve this question. The program, I figured, would permute through all of the legitimate permutations of letters that could be drawn in a game of Countdown, and determine how many words and of what length could be derived from them2. It’d repeat in this fashion, at any given point retaining the worst possible hands (both in terms of number of words and best possible score).

When the program completed (or, if I got bored of waiting, when I stopped it) it’d be showing the worst-found deals both in terms of lowest-scoring-best-word and fewest-possible-words. Easy.

Here’s how far I got with that program before I changed techniques. Maybe you’ll see why:

#!/usr/bin/env ruby WORDLIST = File.readlines('dictionary.txt').map(&:strip) # https://github.com/jes/cntdn/blob/master/dictionary LETTER_FREQUENCIES = { # http://www.thecountdownpage.com/letters.htm vowels: { A: 15, E: 21, I: 13, O: 13, U: 5, }, consonants: { B: 2, C: 3, D: 6, F: 2, G: 3, H: 2, J: 1, K: 1, L: 5, M: 4, N: 8, P: 4, Q: 1, R: 9, S: 9, T: 9, V: 1, W: 1, X: 1, Y: 1, Z: 1, } } ALLOWED_HANDS = [ # https://wiki.apterous.org/Letters_game { vowels: 3, consonants: 6 }, { vowels: 4, consonants: 5 }, { vowels: 5, consonants: 4 }, ]

At this point in writing out some constants I’d need to define the rules, my brain was already racing ahead to find optimisations.

For example: given that you must choose at least four cards from the consonants deck, you’re allowed no more than five vowels… but no individual vowel appears in the vowel deck fewer than five times, so my program actually had free-choice of the vowels.

Knowing that3, I figured that there must exist Countdown deals that contain no valid words, and that finding one of those would be easier than writing a program to permute through all viable options. My head’s full of useful heuristics about English words, after all, which leads to rules like:

- None of the vowels can be I or A, because they’re words in their own right.

- Five letter Us is a strong starting point, because it’s very rarely used in two-letter words (and this set of tiles is likely to be hard enough that three-letter words are already an impossibility).

- This eliminates the consonants M (mu, um: the Greek letter and the “I’m thinking” sound), N (nu, un-: the Greek letter and the inverting prefix), H (uh: another sound for when you’re thinking or hesitating), P (up: the direction of ascension), R (ur-: the prefix for “original”), S (us: the first-person-plural pronoun), and X (xu: the unit of currency). So as long as we can find four consonants within the allowable deck letter frequency that aren’t those five… we’re sorted.

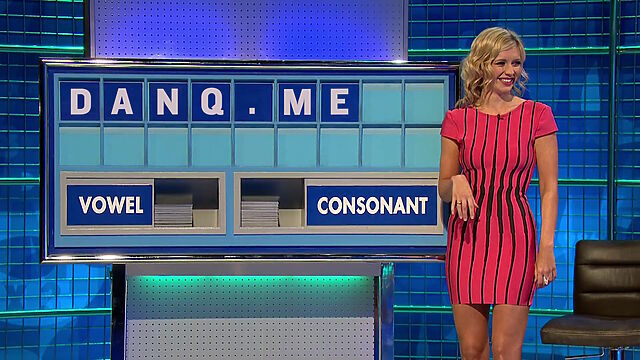

I enjoyed getting “Q” into my proposed letter set. I like to image a competitor, having already drawn two “U”s, a “J”, and a Y”, being briefly happy to draw a “Q” and already thinking about all those “QU-” words that they’re excited to be able to use… before discovering that there aren’t any of them and, indeed, aren’t actually any words at all.

Even up to the last letter they were probably hoping for some consonant that could make it work. A K (juku), maybe?

But the moral of the story is: you don’t always have to use a computer. Sometimes all you need is a brain and a few minutes while you eat your breakfast on a slow Sunday morning, and that’s plenty sufficient.

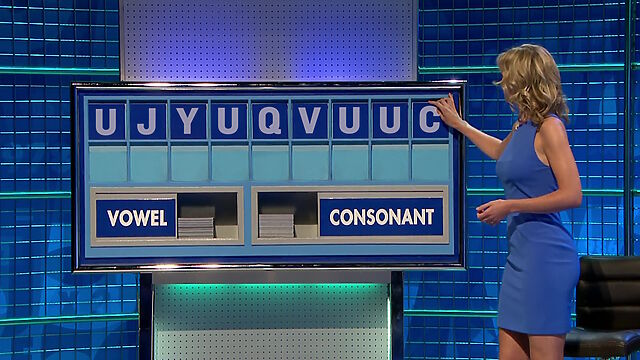

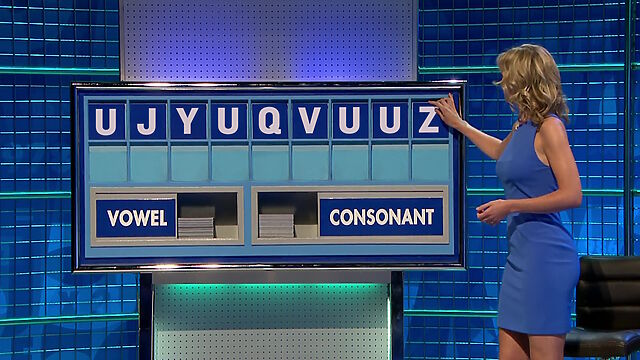

Update: As soon as I published this, I spotted my mistake. A “yuzu” is a kind of East Asian plum, but it didn’t show up in this countdown solver! So my impossible deal isn’t quite so impossible after all. Perhaps U J Y U Q V U U C would be a better “impossible” set of tiles, where that “C” makes it briefly look like there might be a word in there, even if it’s just a three or four-letter one… but there isn’t. Or is there…?

Footnotes

1 It boggles my mind to realise that show’s managed 28 seasons, now. Sure, I know that Countdown has managed something approaching 9,000 episodes by now, but Cats Does Countdown was always supposed to be a silly one-off, not a show in it’s own right. Anyway: it’s somehow better than both 8 Out Of 10 Cats and Countdown, and if you disagree then we can take this outside.

2 Herein lay my first challenge, because it turns out that the letter frequencies and even the rules of Countdown have changed on several occasions, and short of starting a conversation on what might be the world’s nerdiest surviving phpBB installation I couldn’t necessarily determine a completely up-to-date ruleset.

3 And having, y’know, a modest knowledge of the English language

🎗️ Using RSS feeds is a great way to keep up-to-date with my blog. Thanks for subscribing! 🤗