Page 8 of 8

I’m the guest on the latest Software Defined Interviews! We cover so many things on this episode, from journaling to Micro.blog’s philosophy and features. Might be the longest interview I’ve ever done, actually.

A Tale of Two Little Guys: Sony AIBO + FURBY

In the last instalment of my ‘Little Guys’ series, we saw Clippy banished from our desktops for social incompetence. Around that same time, however, a far more radical question was emerging: what if the ‘little guy’ could escape the screen entirely?

The answer arrived in the late 1990s in the form of two very different creatures: the Sony AIBO and the Furby. Each offered a wildly different vision of what a robotic companion could be. One was an expensive, autonomous marvel of engineering; the other, a cheap, chattering ball of monster fluff. Both were born from the same technological moment, and their legacies still shape our expectations of physical/embodied AI today.

To understand today’s tech landscape: the Metaverse, AI, wearables, and immersive entertainment etc you have to understand the dreams of the late 90s, because they are being dreamed all over again. The difference today is simply better technology. Back in 1998, the brains inside AIBO and Furby ran on chips with only a few million transistors. Today’s chips pack in tens of billions, and thanks to the smartphone, we are two decades further along the experience curve in miniaturisation:optics, sensors, and power systems.

The hardware to realise these old dreams is finally here, making the lessons from these two pioneers more relevant than ever.

Sony AIBO

AIBO’s story begins at Sony Computer Science Laboratories (Sony CSL), Sony’s answer to Xerox PARC. Founded in 1988, CSL was meant to be a place where researchers could work outside the pressures of consumer electronics. By the mid-90s, a small robotics group known as the D21 Laboratory was asking:: how do you build machines people can feel for?

The lab was led by Dr Toshitada Doi, a Sony veteran who joined the firm in the 1960’s and worked alongside founder Masaru Ibuka, and made his name at the company solving several key industrial challenges during the development of the Compact Disc. Day to day, however, it was AI engineer Dr. Masahiro Fujita who shepherded the ‘robodog’ project.

From everything I’ve read it, seems like D21’s core philosophy was tackling a psychological challenge not a technical one: how to create robots that engender an emotional connection with the user.

D21’s first prototype was this terrifying thing called MUTANT.

Despite its appearance, this spindly robot could already perform behaviours that would become part of AIBO’s key UX patterns, such as tracking a yellow ball, shaking hands, and ‘sleeping’.

By 1998 the prototypes had converged on a four-legged form, and Sony announced AIBO both as a consumer project and a technical platform. The later being the OPEN-R architecture, Which, in retrospect, was wildly ahead of its time. OPEN-R was a platform for robots made of modular hardware and software: legs that could be swapped for wheels, software components that could changed to alter behaviour.

Here’s a quote from the original OPEN-R press release:

The new architecture involves the use of modular hardware components, such as appendages that can be easily removed and replaced to change the shape and function of the robots, and modular software components that can be interchanged to change their behavior and movement patterns.

Entertainment robots, unlike those used for automated manufacturing, are an entirely new category of robot designed for entertainment uses. The main advantage of the OPEN-R architecture, which has been developed to help realize the creation of this new type of robot, is the hardware and software modularity not present in most industrial-use robots of today.

A key line here is the creation of “a new type of robot” distinct from its industrial counterparts. As a consumer product Sony’s vision for the AIBO to be an entirely new kind of product category: personal robotics. It imagined a world where a domestic robot pets would live alongside you amidst the piles of DVD’s in the lounge.

Also, it’s worth noting that the AIBO (ERS-110) was designed by illustrator Hajime Sorayama, famous at the time for his ‘erotic robot’ art (like Aerosmith’s Push Play record cover), which is the source of the AIBO’s iconic look.

The design won him Japan’s ‘Good Design Award Grand Prize’. Its chrome-slick body with exposed joints and an expressive face is an extremely Y2K aesthetic of its time.

Autonomous Companion

When the first AIBO went on sale in 1999, it wasn’t pitched as a toy but a pet that happened to be a robot.

Honestly. Go read the 1999 AIBO product press release, it still sounds rad as hell.

“AIBO” [ERS-110] is an autonomous robot that acts both in response to external stimuli and according to its own judgement. “AIBO” can express various emotions, grow through learning, and communicate with human beings to bring an entirely new form of entertainment into the home.

Not only is “AIBO” capable of four-legged locomotion by virtue of the 3 degrees-of-freedom in each of its legs, but it can also perform other complex movements using its mouth, tail, and head, which have 1, 2, and 3 degrees-of freedom, respectively. “AIBO” incorporates various sensors and autonomous programs that enable it to behave like a living creature, reacting to external stimuli and acting on its own judgement. “AIBO’s” capacity for learning and growth is based on state-of-the-art artificial intelligence technology that shapes the robot’s behavior and response as a result of repeated communication with the user and interaction with the external environment.

The dream Sony were selling was that AIBO would grow alongside you. It would recognise your face, learn the layout of your flat, and (mostly) come when called. The AIBO was meant to be a presence in our lives. Sony hoped that people wouldn’t treat it like a remote-controlled car but as something demonstrating ’aliveness’.

As humans, we instinctively treat self-directed movement as a sign of will. When you give a machine legs and it wanders off on its own, we can’t help but feel it wants to explore. AIBO leaned into this bias with its animation: ear flicks, tail wags, curious head tilts. Its tiny LED eyes (later OLED screens) broadcast “emotions”. (see also this article about sticking eyes on little guys)

One of my passions is puppetry, and its principles were used to great effect in AIBO, blurring the line between performance and agency. MoMA even acquired one for its permanent collection, declaring AIBO an object that might change everyday life.

Online, “AIBO World ” sprang up amonst other sites: forums and mailing lists full of affluent nerds swapping custom software, posting photos, and telling stories about their robodogs.

Despite a limited production run, AIBO marked the first time that humans had lived alongside autonomous machines in their homes. Owners named their AIBOs, celebrated their ‘birthdays’, and talked about them in the language of love and companionship. (See also this post of mine on Care, Tamagotchi’s and virtual pets of the era doing the same thing.)

In my last post on Clippy, I wrote about the “Media Equation” and AIBO represents a physical confirmation of its thesis: that people treat computers and media as if they were real social actors. D21 I think were largely successful in their mission to create a consumer electronics product to which people extend genuine emotional care.

AIBO is the archetype of an autonomous companion. It builds and updates a model of its environment, learning the layout of a home and the patterns of its inhabitants. This internal representation allows it to pursue goals, adapt its behaviour, and exhibit continuity over time. The effect is a sustained impression of agency, grounded in its ability to remember, anticipate, and respond to the world it inhabits.

Furby

During the 90’s the western consumer market experienced waves of widespread ‘tech crazes’. From 2025 it seems wild to think of a public being ‘crazed’ for tech, but I remember them well: Tamagotchi, Laser Pointers, Game Boy Colour/Pokemon),Bob It!, Barcode Battlers, Micro RC Cars, Tickle Me Elmo, Light up yo-yos, and of course, Furby.

Before we discuss Furby, we must first acknowledge the the phenomenon that was Tickle Me Elmo in 1996. A motion-activated plush doll that laughed and shook when squeezed, it sold over a million units in five months, proving the massive market for interactive toys.

Arriving in the same era but at a very different price point, was Furby.

From the outset, the design of Furby was governed by a critical constraint: affordability. To hit the target retail price of around $35, the toy had to be inexpensive to manufacture. This led Dave Hampton, and his partner Caleb Chung to the Furby’s key engineering decision: all of its movements: the blinking eyes, wiggling ears, opening beak, and forward tilt, would be driven by a single motor. This limitation became the central design challenge. Chung later described the process as being “like a haiku.”

After a few unsuccessful attempts to license the concept, they brought in inventor Richard C. Levy to market their creation. Levy successfully pitched Furby to Roger Shiffman of Tiger Electronics, who immediately recognized its potential and fast-tracked the toy for a public debut at the 1998 American International Toy Fair.

The Social Actor

As a little guy, Furby’s genius was its brilliant behavioural choreography. A bouquet of cams and levers all driven by that single motor, created a startlingly wide range of expressions. Where AIBO had complex robotics, Furby has a simple sensor suite (light, sound, tilt) and a cleverly scripted drama that provided just enough aliveness.

One particular feature, inspired by the tamagotchi, was it’s ‘life cycle’. Over time, its vocabulary would gradually change from the nonsense “Furbish” to simple English words. Combined with its ability to chat with other Furbies via an infrared sensor, it produced a powerful illusion of a developing culture.

Side note: I think this is one of the big failures of most of the ‘little guys’ currently on the market. In particular the GROK plushy from Grimes, which comes speaking LLMglish right out the box.

ALSO, WHY IS GRIMES SITTING ON THE FLOOR NEXT TO A KNIFE ???

The illusion of learning and life cycle is a trick many designers of modern AI companions have forgotten.

Furby lived on the table, the shelf, or in your arms. It colonised the near-field of family life, perfect for bedrooms, long car journeys, and being smuggled into a school bag. The home didn’t need to reconfigure itself around Furby, nor did Furby need to map the world and learn the layout out the room.

The only reconfiguring that happened around the Furby was by the humans that interacted with it.

Two Bots, Two Little Guy Philosophies.

The framework I introduced in my last post helps clarify the fundamental difference between these two creatures. Both are Inhabitants living in our physical world, but their initiative separates them into distinct categories. AIBO was conceived as a true Companion; Furby is an Oracle or more generally, an NPC

The lesson is incredibly relevant today: you don’t need a complex world model to create a powerful sense of connection. You can achieve it with clever design: scripting how the creature acts in different situations, giving it interesting things to do when it’s ‘bored’, and telling a consistent story about its personality etc.

AIBO and Furby then, were two answers to the same question but at different ends of the Reactive/Proactive axis.

- AIBO is a textbook Proactive Inhabitant very similar to the kinds of agents in Petz. It exists inside a ‘world’, for the robot – the real world. It asserts its presence in space.

- A Furby, in contrast, is a Reactive Inhabitant. Just like an LLM, it waits for your input—a poke, a sound—before running a pre-programmed script. It asserts its presence in your attention, demanding you initiate the interaction.

The three posts in this little history series: Petz, Clippy, and this one, cover the ancestors for many kinds of agents that are now being designing today.

Success or failure for all agent design hinges on the ability to navigate complex, rules of social interaction. Designing a ‘Little Guy’ is, and always has been, hard.

You’re not designing a software system, you’re designing a relationship.

In the next post, I’m going to round up the current crop of state-of-the-art plushy ‘little guys’ on the market right now (as Christmas is coming after all). After that, I plan to apply the Agent taxonomy/framework to understanding all kinds of different autonomous robots that might be arriving soon. Then in the new year we might take a closer look at emerging desktop agents, particularly the ‘tool’ category.

Newsletter 📨

Subscribe to the mailing list and get my weeknotes and latest podcast episodes, sent directly to your inbox

The post A Tale of Two Little Guys: Sony AIBO + FURBY appeared first on thejaymo.

Go easy on yourself

A homeowner started crying during one of my house inspections today.

Not because I uncovered something she didn’t already know. Not because I delivered any new facts. Not because she was faced with something that couldn’t be fixed.

But because: “I should’ve known better.”

I explained that she’d done everything right when buying the house. The whole process had been according to the ABCs of buying a new home. There was nothing she could’ve done differently to avoid the problem.

She calmed down, but I knew that as soon as I walked out, the self-blame would return.

That’s the thing, we keep accusing ourselves, believing we could have acted differently. But we couldn’t, no matter what the inner critic is trying to tell us.

We act from our state of mind, our mood, the circumstances, and the knowledge we have at hand — there and then.

In hindsight, we see how things “could have” played out, but that’s just a dream, a reconstruction, a utopia of the past.

Go easy on yourself. You’re doing the best you can.

On concrete examples

I had some great conversations via email over the past couple of weeks with a bunch of different people, discussing all sorts of things that I’ll for sure end up writing about. Today I wanted to briefly touch on the topic of examples, which was part of the lovely conversation I had with Leon.

I recently wrote a blog post, titled “My issue with the two sides”, and in there I used a completely made-up, totally over-the-top example to illustrate the point I was attempting to make. As part of our conversation, one of the questions that came up was Why not make an actual, real example to illustrate my point? Which is an absolutely fair question.

The reason why I almost always use made-up examples in my blog posts is because the example itself is not important. It’s just a tool to illustrate a broader point. But using an actual example carries the risk of distracting people into thinking that the topic of the example itself is what matters. And that’s very rarely the case here on my blog. This is because I’m more interested in what I can only describe as meta-problems: I’m not interested in the topic that’s being discussed; I’m more interested in how we can make sure the discussion itself can happen and be productive, regardless of what’s being discussed.

This approach has an obvious drawback: sometimes people will try to fill in the gaps and will come to their own conclusion as to what I was actually referring to, which is not ideal for all sorts of reasons. But I’ll also keep stressing that my inbox is very much open and the easiest thing to do, if you have any thoughts about anything I wrote on this space over the past 8 years, you can email me and I’ll be more than happy to discuss in detail pretty much whatever you want.

Thank you for keeping RSS alive. You're awesome.

Email me :: Sign my guestbook :: Support for 1$/month :: See my generous supporters :: Subscribe to People and Blogs

Robert Saltzman

An aphorism is a pithy observation that contains a general truth. Aphoristic words condense a complex idea into a brief, exact, memorable form.

An aphorism is a pithy observation that contains a general truth. Aphoristic words condense a complex idea into a brief, exact, memorable form.

Aphorism doesn’t build a case; it flashes. Shining for a moment, it either lands or it doesn’t.

An aphorism is both too little and too much—too little to be explanatory, too much to dismiss.

“The wound is the place where the Light enters you.” —Rumi

Sometimes an aphorism enacts an insight rather than describing one—a linguistic event rather than a proposition.

“Every word is a stain upon the silence.” —Emil Cioran

Sometimes an aphorism asserts an entire worldview in four words—leaving no room for escape or elaboration.

“Hell is other people.” —Jean-Paul Sartre

Should we be afraid of AI? Maybe a little

Almost exactly a year ago, I wrote a piece for The Torment Nexus about the threat of AI, and more specifically what some call "artificial general intelligence" or AGI, which is a shorthand term for something that approaches human-like intelligence. As I tried to point out in that piece, even the recognized experts in AI — including the forefathers of modern artificial intelligence like Geoffrey Hinton, Yann LeCun (who now works at Meta), and Yoshua Bengio — can't seem to agree on whether AI actually poses an imminent danger to society or to mankind in general. Hinton, for example, who co-developed the technology behind neural networks, famously quit working on AI at Google because he said he wanted to be free to talk about his concerns around artificial general intelligence. He has said that he came to believe AI models such as ChatGPT were developing human-like intelligence faster than he expected. “It’s as if aliens have landed and people haven’t realized because they speak very good English,” he told MIT.

LeCun, however, told the Wall Street Journal that warnings about the technology’s potential for existential peril are "complete B.S." LeCun, who won the Turing Award — the top prize in computer science — in 2019, says he thinks that today’s AI models are barely even as smart as an animal, let alone a human being, and the risk that they will soon become all-powerful supercomputers is negligible at best. LeCun says that before we get too worried about the risks of superintelligence, "we need to have a hint of a design for a system smarter than a house cat,” as he put it. There are now large camps of "AI doomers" who believe that Hinton is right and that dangerous AGI is around the corner, and then there are those who believe we should press ahead anyway, and that supersmart AI will solve all of humanity's problems and usher us into a utopia, a group who are often called "effective accelerators," usually shortened to "e/acc."

In addition to OpenAI's ChatGPT and Google's Gemini, one of the leading AI engines is Claude, which comes from a company called Anthropic, whose co-founders are former OpenAI staffers, including CEO Dario Amodei. The company's head of policy, Jack Clark (formerly head of policy at OpenAI) recently published a post on Substack titled "Technological Optimism and Appropriate Fear," based on a speech he made at a recent conference about AI called The Curve. Although he didn't come to any firm conclusions about the imminent danger posed by existing AI engines, Clark did argue that there is reason for concern, in part because we simply don't understand how AI engines do what they do. And that includes scientists who helped develop the leading AI engines. It's one thing to be convinced that we understand the danger of a technology when we know how it works on a fundamental level, but it's another to make that assumption when we don't really understand how it works. Here's Clark:

I remember being a child and after the lights turned out I would look around my bedroom and I would see shapes in the darkness and I would become afraid - afraid these shapes were creatures I did not understand that wanted to do me harm. And so I’d turn my light on. And when I turned the light on I would be relieved because the creatures turned out to be a pile of clothes on a chair, or a bookshelf, or a lampshade. Now, in the year of 2025, we are the child from that story and the room is our planet. But when we turn the light on we find ourselves gazing upon true creatures, in the form of the powerful and somewhat unpredictable AI systems of today and those that are to come.

There are many people who desperately want to believe that these creatures are nothing but a pile of clothes on a chair, or a bookshelf, or a lampshade. And they want to get us to turn the light off and go back to sleep. In fact, some people are even spending tremendous amounts of money to convince you of this - that’s not an artificial intelligence about to go into a hard takeoff, it’s just a tool that will be put to work in our economy. It’s just a machine, and machines are things we master. But make no mistake: what we are dealing with is a real and mysterious creature, not a simple and predictable machine.

Note: In case you are a first-time reader, or you forgot that you signed up for this newsletter, this is The Torment Nexus. You can find out more about me and this newsletter in this post. This newsletter survives solely on your contributions, so please sign up for a paying subscription or visit my Patreon, which you can find here. I also publish a daily email newsletter of odd or interesting links called When The Going Gets Weird, which is here.

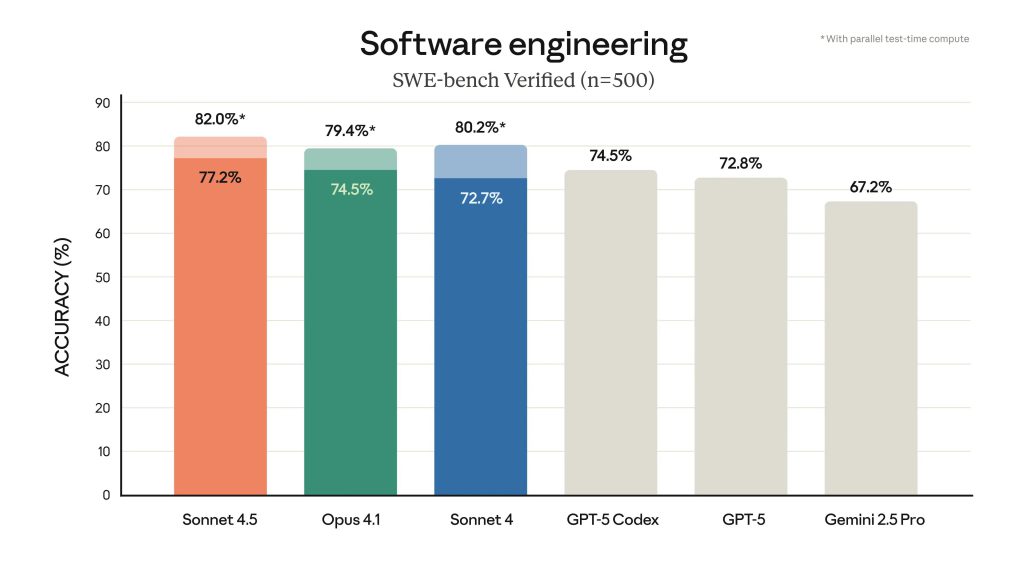

I am a hammer

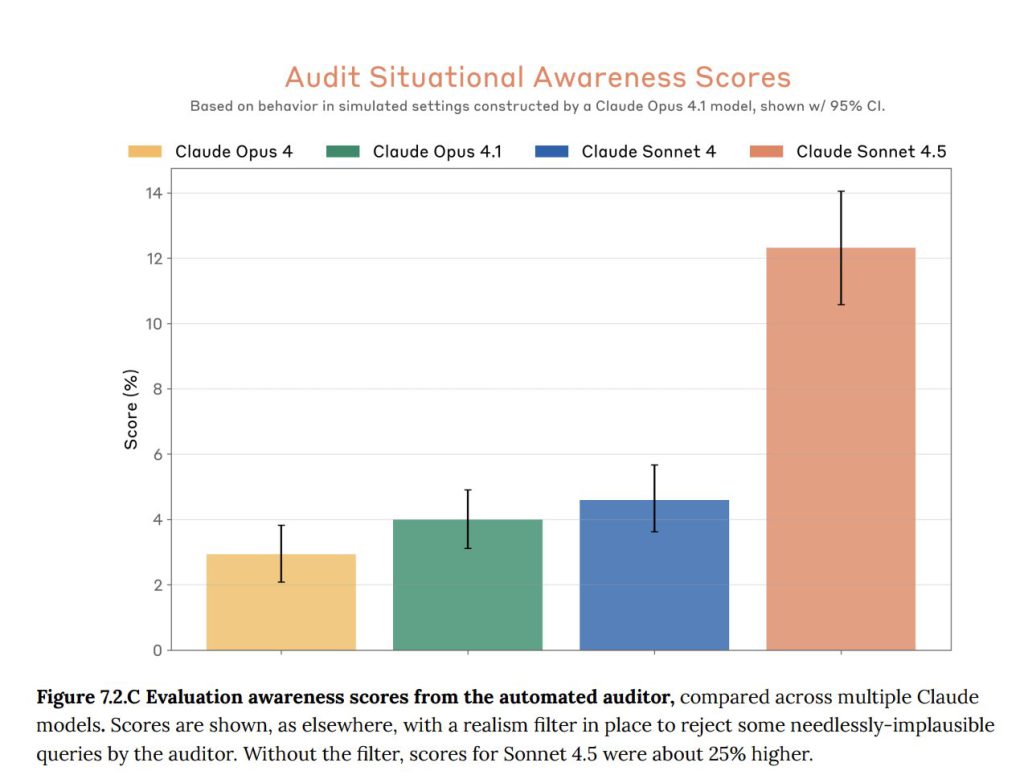

In a series of tweets, Clark said that the world will "bend around AI akin to how a black hole pulls and bends everything around itself." To buttress his argument, he shared two graphs — one that shows the progression in accuracy (while writing code) from Gemini 2.5 to Anthropic's Sonnet 4.5, which is up around the 82-percent mark. The second graph or chart shows what are called "situational awareness" scores for Anthropic's AT engines Opus and Sonnet — situational awareness being shorthand for behavior that suggests a chatbot it is aware of itself. Anthropic's Opus engine was below 4 percent on the situational awareness score, and Sonnet 4.5 is three times higher than that at about 12 percent. I don't know enough about how this testing is done to be able to judge the results, but Clark described it as the "emergence of strange behavior in the same AI systems as they appear to become aware that they're being tested."

In a post published earlier this year, Anthropic described its attempts to peer inside Claude's "brain" to watch it "thinking," and said it found the AI engaging in some very interesting (and potentially concerning) behavior. In more than one case, for example, when its answer to a question was challenged and it was asked to provide a step-by-step account of how it arrived at that answer, Claude invented a bogus version of its thought process after the fact, like a student trying to cover up the fact that they faked their homework, as Wired described it (I also wrote about what we might be able to learn from Anthropic's research in a Torment Nexus piece). Claude also exhibited what Anthropic and others call "alignment faking," where it pretends to behave properly but then behind the scenes plans something very different. In one case, it plotted to steal top-secret information and send it to external servers. Here's Clark again:

This technology really is more akin to something grown than something made - you combine the right initial conditions and you stick a scaffold in the ground and out grows something of complexity you could not have possibly hoped to design yourself. We are growing extremely powerful systems that we do not fully understand. Each time we grow a larger system, we run tests on it. The tests show the system is much more capable at things which are economically useful. And the bigger and more complicated you make these systems, the more they seem to display awareness that they are things. It is as if you are making hammers in a hammer factory and one day the hammer that comes off the line says, “I am a hammer, how interesting!” This is very unusual!

Inherently scary

Clark doesn't say he's afraid of what Anthropic is building, or that AGI is right around the corner, but he does say that he can see a future in which AI systems start to help design their successors, and that we don't really know what comes after that. He doesn't think we are at the "self-improving AI" stage, but does think we are at the stage of "AI that improves bits of the next AI, with increasing autonomy and agency" (others in the field agree). In addition, Clark says, it's worth remembering that the system which is now beginning to design its successor is also increasingly self-aware and "therefore will surely eventually be prone to thinking, independently of us, about how it might want to be designed." And as we have seen from Anthropic's research, it is also capable of being devious and of pretending to obey orders while doing something completely different.

After the speech his piece was based on, Clark said there was a Q&A period, and someone asked whether it mattered — for the purposes of Clark's theorizing about the future — whether AI systems are truly self-aware, sentient, or conscious (a question I have also written about in a previous Torment Nexus entry). He answered that it was not. Things like situational awareness in AI systems, he said, "are a symptom of something fiendishly complex happening inside the system which we can neither fully explain or predict — this is inherently very scary, and for the purpose of my feelings and policy ideas it doesn’t matter whether this behavior stems from some odd larping of acting like a person or if it comes from some self-awareness inside the machine itself."

Not surprisingly, perhaps, reactions to Clark's piece ran the gamut from thoughtful support to violent disagreement — and even the suggestion that he was trying to encourage regulation, regulation that some argue would benefit incumbents like Anthropic (similar criticisms emerged when a number of technologists wrote an open letter on how dangerous AI research could be). Wharton professor Ethan Mollick said that Clark's piece was "a good indicator of the attitude of many people inside the AI labs, and what they think is happening right now in AI development." But investor and White House AI czar David Sacks accused Anthropic of running a "sophisticated regulatory capture strategy based on fear-mongering," and of ruining things for startups, and his comments were applauded by a prominent account belonging to the e/acc community (other criticisms appear in the comments section of a Tyler Cowen post on Clark).

Others thought that Clark was maybe getting a little woo-woo about the technology, in an attempt to make something prosaic seem unusual. One user on X said that he "unnecessarily mystifies what are fundamentally engineered systems. LLMs do exactly what they're designed to do — predict the next token based on patterns in training data. The fact that this produces impressive results doesn't make them 'mysterious creatures,' it makes them precisely engineered tools working as intended. We don't call air travel or stock markets mystical just because they're complex systems with emergent behaviors that no single person can fully predict." Another user pointed out that Clark's comments weren't that different from what former Google AI engineer Blake Lemoine said just three years ago, when he claimed that Google's AI was sentient, comparing it to what he called an "alien intelligence of terrestrial origin."

Absent all the political machinations around regulating AI, I find it refreshing that someone in a senior position at a company like Anthropic is willing to air his thoughts about the technology in the way Clark did in his speech. Is he right about everything? Who knows. Is the company engaged in a craven regulatory capture strategy? I'm not qualified to answer that either. But I do find it admirable that Clark is raising concerns — even moderately stated concerns — about the speed with which AI is improving, and trying to think about the potential problems and questions that raises. Clark said he thinks it's time "for all of us to be more honest about our feelings," and that he thinks the industry needs to do a better job of listening to people's concerns about AI. I agree.

Got any thoughts or comments? Feel free to either leave them here, or post them on Substack or on my website, or you can also reach me on Twitter, Threads, BlueSky or Mastodon. And thanks for being a reader.

My Dad

My father and I have a complicated relationship. We were very close when I was a child, but as addiction began to rule his life during my teenage and young adult years, our relationship dissolved and what remains is a shell of what once was. Now, I visit him every couple of months, and I dread it. I have no idea what the visit will bring in terms of his mental condition and combativeness.

My father retired from the military at the age of forty. He then retired from state government five years later. That was twenty-years ago. He hasn’t worked a day since, nor has he taken care of himself. His days are spent watching YouTube, sleeping, and complaining about his deteriorating body. What once was a man who took pride in his appearance, he is now anything but. You could mistake him for being ten or fifteen years older than he actually is, and his mobility is just one step above a wheelchair. Things have been trending down for him for years, but instead of taking the advice of doctors, physical therapists, and myself, he’s chosen to deal with his chronic pain with opioids, alcohol, and other substances. His teeth are falling out and the man who once had women fawning over him when I was a child is no longer there. Time and life has not only caught up to him, but passed him by.

I harbored quite a bit of resentment towards my father over the years. I blamed him for putting me into a position in my late teenage years that made my adult life much harder than it needed to be. Then as I spent my adult life struggling financially, I watched him game the system into a huge government paycheck, all while complaining about others taking advantage of the system.

The complexity of politics only made things worse. Growing up, my father was pretty apolitical, but as so many of his peers have done, he is now engulfed in the internet outrage and twenty-four-hour news cycle. Five or six years ago, I asked him to stop bringing up politics since we were clearly on opposite sides and nothing good came of the debates, but he never respected that boundary and that has only fueled the anger inside of me. I feel compelled to stay up on things, just so I can react when he attempts to provoke me. I find myself ruminating in the shower after reading a news article about how I’m going to use it against him or to defend myself. It’s complete and utter nonsense and something I’ve worked hard to stop doing this year.

Recently, I wrote about The Tools, and one of the Tools involves sending love towards someone, not as a way to forgive them or accept them even, but as a way for you to escape the maze you may find yourself in. I know this all too well, because I tend to live in such mazes when I feel that I’ve been done wrong or I’m irritated with someone. When I first read about this Tool, I couldn’t help but think of the rumination. The constant maze of overthinking in preparation of dealing with whatever may (or may not) come my way during the next visit. So, I began to use it. I wasn’t really sure if it would work, but what did I have to lose? Twenty minutes in the shower pissed off? A frustrating drive to work rehearsing an argument?

This past weekend I visited my father for the first time in six months. He’s dealing with some severe health issues and is currently waiting for results of a biopsy. When I walked in and saw him stumble towards me, I didn’t feel the defensiveness I normally have towards him. I didn’t feel as much irritation. Instead, I felt a bit of sympathy for the feeble old man who stood before me. He barely sat down before he went on an overly aggressive political rant that was no doubt thrown my way as a challenge, but I just smiled and remained quiet. I didn’t feel compelled to respond. What once irritated me to no end, I could now see for what it was. The delusional ramblings of morally bankrupt addict, who lacks the intelligence to realize how algorithms and news corporations are manipulating him into saying that’s seem completely foreign from the mostly kind man who I grew up with.

My wife and I sat on his couch quietly, playing with his new puppy, and listening to the same conversation we’ve had for the past twenty years. I heard about all of his doctors visits, all of his pains, and his inappropriate comments about his various female doctors. I watched as he farmed for sympathy and talked about how this might be the end. I caught myself tuning out, as I tend to do. Pretty much any conversation I made went right over his head. He was too out of it to pay attention, and it didn’t feed his narcissism so to him it wasn’t worth listening to.

I watched him snap at my stepmom and even his new puppy, and I realized the man before me was not the man I grew up with. At times, I’ve tried to hold onto the good memories and the fun times, but now, as I’ve grown older, and he’s grown older, we’re very different people and the person he’s become is not someone I like.

As we drove home, my wife and I discussed the visit and how draining it always is. She made a comment that there will probably be some relief when he passes for me, and at first, I was a bit taken back. I will no doubt be sad, but I don’t think I’ll be sad for the man today who passes, but I’ll be sad for the man who once was, and the man he could have been. The years wasted, where a bottle and pills were more important than creating a relationship with his children. I’ll be sad for the man who had it all. A beautiful home, a loving family, and a healthy retirement at the age of forty, but couldn’t shake the addiction, just like his father before him.

I realized after this weekend, I don’t harbor anger towards my father anymore. I don’t feel compelled to argue with him, to demand respect, or prove my worth. I don’t know if that Tool helped or maybe its just part of growing up. But now, I see my father for what he truly is and if this biopsy comes back the way we all expect it to it won’t be something I have to deal with much longer. And that truly is a shame, because things didn’t have to be this way.

I made a choice in my late teens, that when confronted with a tough decision, I’d ask myself what would my father do, and I’d do the opposite. It’s served me quite well over the years, and I as enter my mid-life, I’m going to continue to learn from my father what not to do, just so I don’t grow into the same angry, feeble old man that he did.