Managing our social connections beyond Dunbar.

While aspects of our behaviour on social networks can reflect that of our offline lives we need not be subject to the same constraints.

Social networks are often criticised for being little more than online popularity contests where users strive to amass ever higher numbers of followers. The pressures of online influence systems demanding constant interaction with an ever wider reach also contribute to this feeling and we are advised that we should focus on quality and not quantity.

Social networks are often criticised for being little more than online popularity contests where users strive to amass ever higher numbers of followers. The pressures of online influence systems demanding constant interaction with an ever wider reach also contribute to this feeling and we are advised that we should focus on quality and not quantity.

The argument most frequently used to "prove" that having a larger number of friends online is impossible is that proposed in Dunbar's Number: the "theoretical cognitive limit to the number of people with whom one can maintain stable social relationships". Dunbar's research concludes that the maximum sized group an individual can successfully socialise with to a meaningful degree is based on the size of the neocortex (a part of the brain in mammals). While Dunbar's number is actually a range between 100 - 230 it is generally put at an accepted figure of 150.

Social networks are said to be incompatible with this research due to the constant pressure to gain ever higher numbers of followers or "friends" as we cannot hope to maintain a meaningful relationship with the hundreds or thousands that we may connect to.

Models

As I have mentioned previously, there are different social (or friending) models that can be applied to social networks which, themselves, will influence the way we deal with our connections so why is Dunbar's number consistently quoted when dealing with the number of friends and followers on social networks?

The three primary models that we can apply to social are:

- friending, where both parties know and mutually follow each other,

- following, a unilateral act of subscribing to someone's updates which may be reciprocal, and

- interest, where we will follow a topic rather than a person

The most instantly recognised example of the friending model is, of course, Facebook but the ability to subscribe to individuals and lists may serve to make the act of friending irrelevant except in the most specific of circumstances.

Gathering followers and following others are not, in themselves, contrary to Dunbar; having many people follow your updates, or subscribing to the updates of others, is not a "friend relationship" so, in theory at least, we can follow and have as many followers as we like.

Problems arise when we start directly reciprocating a follow with a view to greater engagement but, here too, we can make a distinction between the friending and following models. How we view our connections in social sites will determine how we interact with them and whether we choose to divide them into groups in order to facilitate a friend-type relationship.

Groups, lists and circles are ideal at helping us to separate our core friends with whom we can establish more meaningful relationships.

The new news

With the increasing move away from traditional media through subscribing to RSS feeds to using curation via social networks we are making a distinction between those we follow primarily for information purposes and those with whom we aim to have a closer bond. Following more than Dunbar's number on a social network need not mean we are trying to manage more "friends" but that we are treating them as a "news source".

The act of curation is multi-levelled – we curate those individuals who curate information from varying sources which, in turn may include other curators, and so on – and does not imply any form of engagement. We can therefore actively follow the updates of many without any pressure to actually interact with them.

It is in our nature, however, to engage but that level of engagement will vary based on the individual and the relevance of the specific content being curated.

Context

Dunbar's number defines only our closest connections and does not contain those who are known but "with a lack of persistent social relationship" – a definition which covers our more casual social acquaintances - so, once again, why is Dunbar's number consistently quoted when dealing with social networks?

Dunbar argued that 150 would be the average group size only for those communities with a very high incentive to remain together (a village or tribe relying on each other for survival, for example) and “that as much as 42% of the group's time would have to be devoted to social grooming.”

Consequently, such groups are almost always physically close: "... we might expect the upper limit on group size to depend on the degree of social dispersal. In dispersed societies, individuals will meet less often and will thus be less familiar with each, so group sizes should be smaller in consequence."

Dunbar has suggested that while we may have hundreds or thousands of connections on a service such as Facebook we will still keep a core list of 150 friends. As our interactions on social networks are scattered and varied, spread across multiple time zones and impacted by offline pressures such as family life and work it would seem reasonable that we would instead be far more likely to have a core "friends" group much lower than the 150 we are repeatedly quoted.

Is this why the first version of the social app Path originally launched with a 50 person friend limit and is it now, perhaps, being unrealistic by increasing that to 150 to confirm with the social norm? Or is Path the exception as it is designed to be used by existing groups of offline friends who are already a closely knit group?

Who are our friends?

While the term “friend” has been diluted by its adoption in social parlance who are these core people Dunbar is referring to? With whom do we want and need to maintain such strong relationships?

Family and close friends (perhaps from school or university) are obvious examples of such groups and it has also been suggested the number could include past colleagues or associates with whom we might want to become reacquainted. Work colleagues acting as a close team in a small organisation are also commonly suggested. These groups are an obvious fit when dealing with a service such as Facebook as the online experience will equate directly to the offline.

As Dunbar’s number relates to “relationships in which an individual knows who each person is, and how each person relates to every other person” it is obvious that we are talking about distinct social groups – a situation that is often not mirrored by our use of social networks.

Once we get beyond our immediate circle of friends we accept that the connections we make will be predominantly casual with no persistent social relationship so will not impede upon our cognitive ability to closely interact with a set number of individuals.

Ever decreasing circles

In life we drift through implicit social circles based on interest or location without even realising we are doing it and our experiences on social networks follow similar patterns despite explicitly following other users.

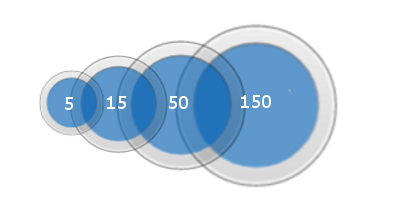

As our social circles expand so the degree of intimacy must necessarily decrease. Our core group of 150 is divided into four Circles of Acquaintanceship of increasing sizes from 5 intimate connections through successive groups of 15 and 50 to the full 150. At each level we will know less about the individuals within that group as their number increases. As our relationships change with those individuals they may migrate from circle to circle.

This logic extends beyond the limits of Dunbar’s number and it has been suggested that circles of acquaintanceship continue to 500, 1500 and beyond. Coincidentally, 1500 is apparently the number of faces we can easily recognise.

By using groups, lists and circles we organise our connections based on relationship and interest and may often find ourselves building a core list of users, or engagers, with whom we interact most frequently.

Our interactions with some may drop off as we drift apart or lose the common interest which prompted us to initially connect, ultimately leading us to remove them when periodically tidying up our lists – we lose touch with people when we are no longer exposed to them.

On other occasions we will become more familiar with others as we interact with them more frequently, sometimes extending this interaction offline. Just as in "real life", this process will serve to promote individuals up through our circles of acquaintanceship and can potentially even move them into our core group of friends.

Familiar but not limited

The principals behind Dunbar's number can be recognised in our activity on social networks but, by managing our connections, we make it largely irrelevant as long as we under no illusion that we must interact constantly and equally with all of our connections.

The tools we have at our disposal now negate the use of Dunbar's number as an argument to not building an extensive social circle but we must recognise that, even on social networks, we will inevitably have those with whom we interact on a more frequent basis due to their relevance and interests.

Lead image by JDConway

John shared a post by Doc Searls from back in February that I had missed - Doc blogs in a couple of different places and this was one I didn't have in my feed reader. In it Doc shares his thoughts about blogging now in contrast with how it used to be at the "dawn of blogging's golden age." A couple of points really connected with me. Firstly, he remarks that this "age" "seems to have come and gone: not away, but... somewhere." I'm not sure if that's wishful thinking or an allusion to a recent rekindling in old school blogging, people trying to get back to how they used to write and interact, having got temporarily lost in the social age. This leads to the next point which struck home:

He goes on:

This is exactly how I feel the landscape has changed, and as I've mentioned before. The chances were that much of our readership also used to be bloggers so the author/reader relationship was widely reciprocated. Even those that weren't bloggers used to be heavily engaged, regular commenters who would leave substantial replies to posts. It was common to say that the comment sections on blogs were just as, if not more, valuable than the posts themselves. Such was the care, thought and consideration put into them. You felt like you knew your readers and those bloggers, in turn, that you were a reader of. But social killed much of that. Social platforms claim to be powered by engagement but it's the wrong kind of engagement, the minimum social actions which are more advertisements for presence and "me too" curation fodder showing off the supposed breadth of someone's reading. It's ironic that the more we are supposedly connected the more distant we become. Perhaps we are widening the circles of acquaintanceship too far. We used to focus on our comment sections and those of a select number of blogs we subscribed to, and the intimacy we experienced with our core contributors gave a real sense of community. That feeling is often replicated in the early days of new platforms and services when user numbers are low and you would see the same names and avatars all the time. Think Twitter, FriendFeed, Buzz, Google+ - even though it was called a wasteland the initial sense of community was amazing. Each had that "new frontier" aesthetic for their devotees; the untamed badlands to be shaped in our image until they, the great unwashed, discovered it and suddenly the quaint little settlement, where everybody knew everyone else, became full of noise and traffic and strangers. You can't argue when Doc says that it's "harder to blog when there is very little sense of connection anywhere outside of tweets and retweets, which all have the permanence of snow falling on water." Such a powerful statement. But I keep coming back to the notion that the golden age has not gone away, but... somewhere! Where exactly? Doc says he's "not sure yet" but I think he's got an inkling which is why he phrases it in such a way. Here's what I think: The where is with those like himself who, despite it all, kept posting to their blogs even if the engagement wasn't there because it was what they understood and believed in. It's with the backlash against the new tribalism of social networks, the desire to return to proper conversations rather than playground name calling and increasingly dangerous rhetoric. It's with those who strive for an open, connected web allowing people to express themselves outside the walls and control of silos and corporate control. There are pockets of "where" spread across the web - we just need to find them.

John shared a post by Doc Searls from back in February that I had missed - Doc blogs in a couple of different places and this was one I didn't have in my feed reader. In it Doc shares his thoughts about blogging now in contrast with how it used to be at the "dawn of blogging's golden age." A couple of points really connected with me. Firstly, he remarks that this "age" "seems to have come and gone: not away, but... somewhere." I'm not sure if that's wishful thinking or an allusion to a recent rekindling in old school blogging, people trying to get back to how they used to write and interact, having got temporarily lost in the social age. This leads to the next point which struck home:

He goes on:

This is exactly how I feel the landscape has changed, and as I've mentioned before. The chances were that much of our readership also used to be bloggers so the author/reader relationship was widely reciprocated. Even those that weren't bloggers used to be heavily engaged, regular commenters who would leave substantial replies to posts. It was common to say that the comment sections on blogs were just as, if not more, valuable than the posts themselves. Such was the care, thought and consideration put into them. You felt like you knew your readers and those bloggers, in turn, that you were a reader of. But social killed much of that. Social platforms claim to be powered by engagement but it's the wrong kind of engagement, the minimum social actions which are more advertisements for presence and "me too" curation fodder showing off the supposed breadth of someone's reading. It's ironic that the more we are supposedly connected the more distant we become. Perhaps we are widening the circles of acquaintanceship too far. We used to focus on our comment sections and those of a select number of blogs we subscribed to, and the intimacy we experienced with our core contributors gave a real sense of community. That feeling is often replicated in the early days of new platforms and services when user numbers are low and you would see the same names and avatars all the time. Think Twitter, FriendFeed, Buzz, Google+ - even though it was called a wasteland the initial sense of community was amazing. Each had that "new frontier" aesthetic for their devotees; the untamed badlands to be shaped in our image until they, the great unwashed, discovered it and suddenly the quaint little settlement, where everybody knew everyone else, became full of noise and traffic and strangers. You can't argue when Doc says that it's "harder to blog when there is very little sense of connection anywhere outside of tweets and retweets, which all have the permanence of snow falling on water." Such a powerful statement. But I keep coming back to the notion that the golden age has not gone away, but... somewhere! Where exactly? Doc says he's "not sure yet" but I think he's got an inkling which is why he phrases it in such a way. Here's what I think: The where is with those like himself who, despite it all, kept posting to their blogs even if the engagement wasn't there because it was what they understood and believed in. It's with the backlash against the new tribalism of social networks, the desire to return to proper conversations rather than playground name calling and increasingly dangerous rhetoric. It's with those who strive for an open, connected web allowing people to express themselves outside the walls and control of silos and corporate control. There are pockets of "where" spread across the web - we just need to find them.