The problem with Stoicism

Some call Stoicism overly negative as its adherents go with the flow and accept whatever happens to them as the natural order of things.

The modern bastardisation of the very word stoic to mean unfeeling, emotionless is a perfect illustration of how it is perceived from the outside.

The Stoic way is to acknowledge "life" as the true path, no matter what, realise that it is our role to ensure that the correct result occurs and live a good life along the way. A good life in this context meaning in accordance with the natural order (see Choices, always choices.)

Stoicism teaches that we must see everything for what it is, recognise its true form and only acknowledge this.

The usual response is that this actually releases us; the removal of attachment to things beyond ourselves is supposedly the greatest freedom. The Stoic wants to see things as they truly are - deliberate, blunt - rather than be naive and ignorant.

But Stoicism is quite reductionist, not in the extreme sense of monism, but in its quest for clarity.

More than thought

Stoicism has been described as the philosophy, even the religion, for slaves and for the military - it is easy to see why. There is an element of separation, of removing yourself from the influence of external forces which would be extremely beneficial in such stressful circumstances.

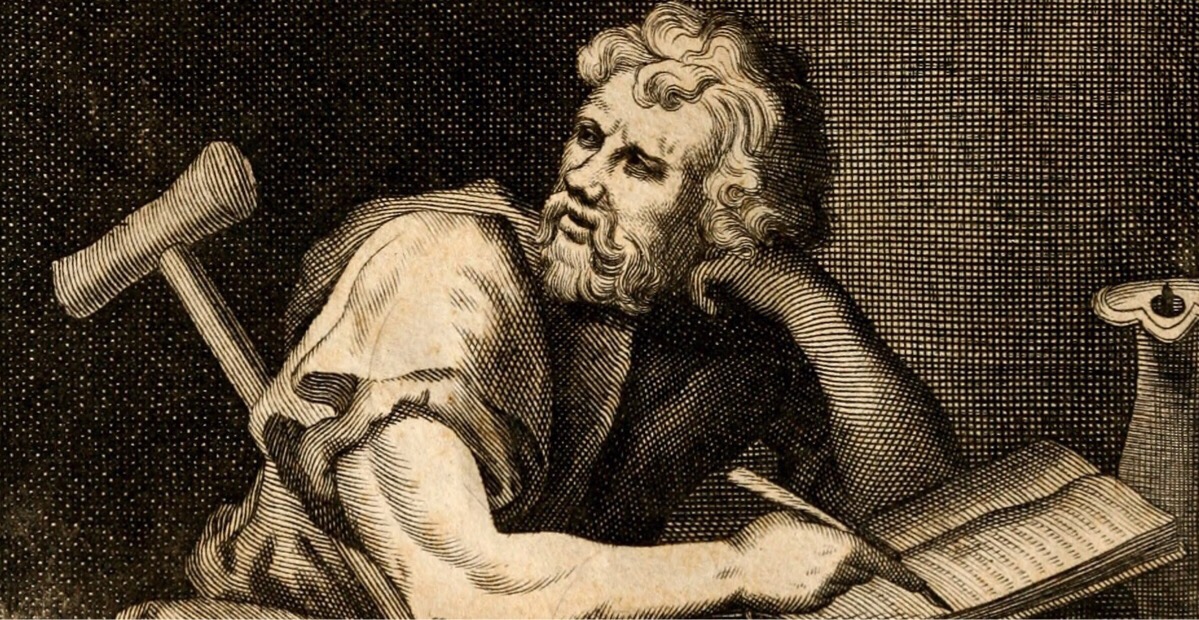

Indeed Epictetus, one of the preeminent stoic voices, was himself a slave during his early life so this path would have appealed greatly, just as it would to those seeking solace from the horrors of war.

Rather than just a school of philosophy Stoicism is considered a way of life: how to behave in, and respond to, the world - a nontheistic religion of sorts.

This may work in extreme environments but can it really apply to (and can it be lived in) modern society?

Uncertainty

But I think the actual problem with Stoicism is that it seeks to remove the mystery. Yes, clarity has a beauty all of its own but there is a joy, excitement and anticipation in not knowing.

The freedom to dream, to interpret, to question all lie with exploration, discovery and ambiguity.

This is not to say that we can't learn valuable lessons and gain precious insight from Stoicism. Just as with other philosophical schools, certain aspects make a good deal of sense and anything which prompts consideration of our attitudes and behaviour can only be a good thing.

Perhaps not being a true adherent, and not living it day to day, I am blinded to its true nature.